LB Thompson — American Poet and Creative Writing Instructor at The New School

[Transcript of video]

I was really excited to participate in this project. I knew that I wanted to use the phone as an instrument to try to find a sample of poetry to observe and present.

I was thinking about what sample group of people is this phone going to really resonate with meaning as an object for. And I thought of Pen America Organization here in New York who has a prison mentorship program where people are writing poems and corresponding with mentors. Every year there’s a contest and the winning poems are published online and elsewhere.

I got in touch with friends who work at at Pen America, and got a list of about 60 names and addresses of people writing poems in prisons across the United States. I wrote a letter, which I sent to that list of people, asking them to try to call the phone. I had plugged my phone into a landline at my house. It worked and my phone service provider — its parent company is Altice — has an automated voicemail program. Anyone who calls the phone, if I don’t pick it up, gets the voicemail and the voicemail makes a recording.

I thought, that will be the way I can record poems: have people call in and make a recording of themselves reading their poems. I would hopefully get to hear the voices of the people reading their own poems. There were a few different impediments to this — most of which were institutional. Different prisons in different states have different rules about calling. Most prisons require collect calls and my phone company has blocked all collect calls, so I couldn’t receive a collect call on my phone.

I called the phone company and had a conversation with someone asking about the policy of blocking collect calls. I said, what do people do if they need to communicate with someone who’s in a correctional facility and they live in this area? Because this phone company really dominates where I live on eastern Long Island. They said, you have to switch phone companies. There’s no way, we can’t lift the block. You just can’t accept a collect call. So in my letter I asked the writers if they could try to use a calling card or find another way to get through to the phone and, much to my delight, many of them did. Or not many, but I got four calls with poems.

The people had to be creative about how to get through, if they did. And in my letter I also said, if you can’t get through feel free to mail me your poem and I will invite a fellow writer to read your poem and record their voice doing so. Today, I wanted to spend most of our short time here playing you the recordings that came through from three of those writers.

The first writer is a man named Matthew Feeney, who’s calling from Moose Lake, Minnesota and he was unable to get through. The first part of the video you’ll hear is his attempt to get through. I can hear his voice just for a second saying, this is Matthew. Then his mother called back and recorded his poem. He also mailed me a copy of the poem, so it’s going to appear in the video — and a letter as well. He sent me a letter, so I know more about this first poet than I do about the subsequent poets.

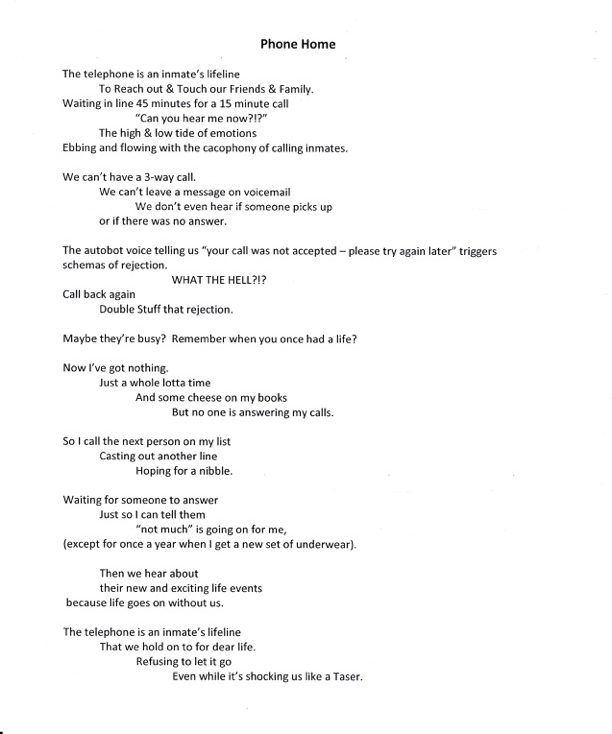

Let’s meet Matthew Feeney and his mother, Jean, and hear his poem which is called “Phone Home”. In my letter, I said you’re not limited in subject matter or length of the poem, just send me any poem to observe. Most people ended up writing about communication, about the challenge of communication with the outside from inside a correctional facility.

“Hello, this is a prepaid debit call from “Hey it’s Matthew”, an inmate at the Minnesota Department of Corrections Moose Lake Correctional Facility. To accept this call press 0, to refuse his call hang up or press 1, to prevent calls from this facility press 9. Your call was not accepted. Please try again later.”

“This is Jean Feeney. I am reading a poem written by Matthew Feeney living in Moose Lake Minnesota. The poem is entitled “Phone Home”.”

I’ll just add that if the phone was ringing and I happened to pick it up — thinking that there might be a chance that I could have a conversation with someone calling from prison — I was unable to answer those calls because there is this autobot that Matthew is talking about in his poem. It is a system that requires someone to pick up and press a number to activate the call. But on this phone you don’t press anything. Everything is a dial, and the technology is incompatible with the software through my phone company. If I picked up and I heard the autobot and I do the rotary dial and wait for it to go through, it didn’t register. I wasn’t able to answer any calls. Matthew also says in his poem that there are no three-way calls, but that must be specific to his facility in Minnesota, because the other calls seem to be three-way calls, as you’ll hear.

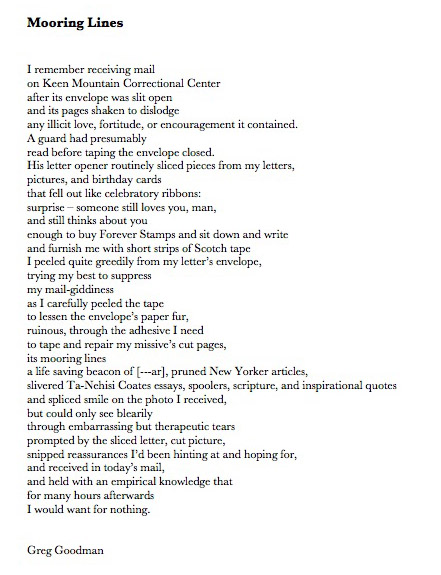

The next call is from a man in Virginia named Greg Goodman:

“Hi my name is Greg Goodman, I’m an incarcerated veteran, and the name of my poem is “Mooring Lines“.

Goodman’s poem addresses the issue of this phrase, there’s no reasonable expectation of privacy for prisoners. Their mail is read, their phones or their calls are monitored, and that was an interesting aspect of the way the phone is used for them to communicate. It remains for that population a communal object. Whereas most of us now have an individual object, a very private experience of having phone calls. We are not anchored to one particular place, either. They have to wait in line, everyone’s using the same phone. I noticed that in New York City — our pay phones seem to have the same handset, the Dreyfuss handset. I was wondering if the people calling me are holding the same design handset from Henry Dreyfuss as they are trying to make the call.

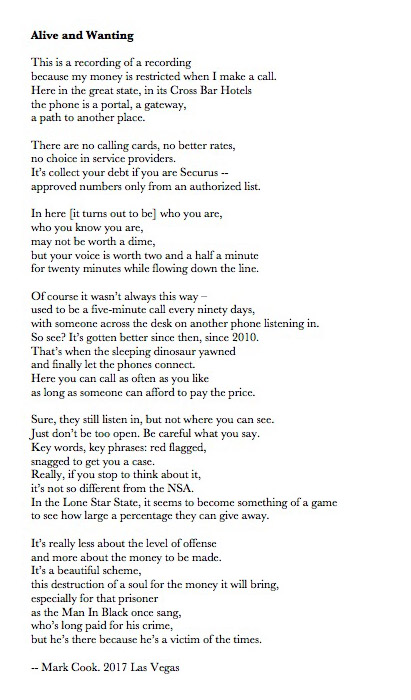

I will play you one more poem. The sound quality in this one was poor and I tried to edit it, clean it up a little bit, so that you can hear it. Each stanza will appear on the screen so that hopefully anything that’s hard to hear, you’ll be able to understand. This writer was not on the list of Pen America participants. I think he must have heard about it from someone else. And I’m not entirely sure that I’m understanding the pronunciation of his name, I have a little more research to do to find him. We know he’s in Las Vegas. It sounds like he’s saying Greg Cook to me. You can tell me what you think you’re hearing.

One question is, who’s profiting from the inflated rates on these calls. There are basically three big telecommunication companies: Securus who he mentions in the poem, Global Tel Link, and CenturyLink. And they are multimillion dollar private equity firms for the most part. One of them, CenturyLink, is the third largest communications company in the U.S. behind AT&T and Verizon, and they reported a net income of $626 million in 2016. The FCC imposed a cap on long distance calls, or interstate calls, in 2013, and those calls are capped at 21 cents. But there’s no cap on Intrastate calls, which is what 85 percent of the calls made from prison are within that state. Those rates vary. The lowest rates are in Delaware, it’s 60 cents a minute or 60 cents for a 15 minute call, and highest in Kentucky, where an instate call costs five dollars and 70 cents a minute.

In the letters that I received from the writers, they told me what they earn and what they have to use the money that they earned for. Any calls that they make need to come out of those earnings and calling cards — if your facility allows calling cards. They have to be purchased in ten dollar increments. Sometimes what they’re making per month is about 15 dollars. Sometimes it’s more like $50 and that’s where you get money for things like aspirin — which one of the people writing to me mentioned specifically is something that he needs to use his funds for. I plan to write back to everybody who I received a letter from and let them know that we heard their poems.

I’m making available all the poems I received in the mail. Two more poems came through the phone this week. I was thrilled that anybody was able to get through and that we have these poems to observe and to learn about — the line in the project description — “expose unseen histories and speculate about the future of the country.” I was trying to expose something unseen. It’s difficult for us to know what is going on, what people are thinking and writing in this situation. Now we have a little bit more of a view. And I think I leave the speculation to all of us who have been able to observe the poems that we got. Thank you.

LB Thompson

LB Thompson has received awards from the Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation, and the Rona Jaffe Foundation. Her poems and essays have been published in The New Yorker as well as other literary magazines and websites. Her collaborative works with visual artist Ellen Wiener have been exhibited recently at Vanderbilt University and The Center for Book Arts. She teaches writing and literature at The New School, and at Suffolk County Community College.