Alexander Robinson is a landscape architect, researcher, and scholar. His work seeks to reinvent our most consequential anthropogenic landscapes through collective authorship, multidisciplinary tools, and community engagement.

As an Associate Professor in the University of Southern California’s Landscape Architecture + Urbanism program, he researches how civic infrastructure can function as landscape, exploring methods to re-envision ecological function and community value.

oorscapes.com

Transcript

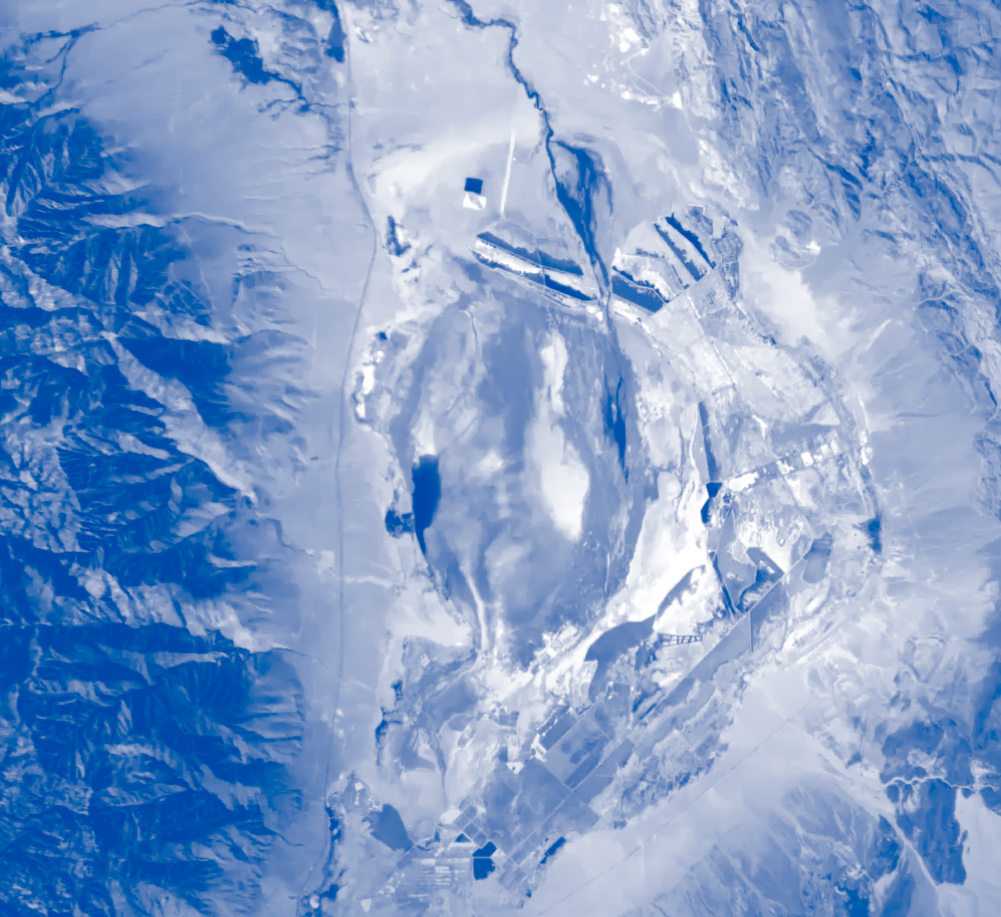

I’m going to give you some background on my practice, then get into the field research that I did on the glass of water. As a landscape architect, I often study and do field studies on altered water-based landscapes, such as the dry Owens Lake, which you’re looking at here.

“Astronaut photograph” of Owens Lake taken from the International Space Station on August 30, 2011, 21:21:37 GMT with a Nikon D2Xs digital camera by the Expedition 28 crew. By ths time, diverse dust controls almost entirely surround the Owens Lake remnant hypersaline brine pool on the north, south, and east (right) sides. In this photograph, many of the dust control cells are dry due to a dust ”season” that only runs from fall to spring.

(Photo courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center, ISS028-E-35137)

This lake was reinvented to control dust rather than being refilled. Also, the Los Angeles River, which you also see in my background, is a river that was infamously distorted into a concrete form to serve as a flood control structure.

These are formerly natural landscapes that are now large civic infrastructures, designed to serve specific standards—often metric standards—at very large scales. For scale, you can see a shopping cart in the middle of this image.

At Owens Lake, in particular, I investigated the connection between how we measure landscape and its making. Owens Lake is a monument to its measurements.

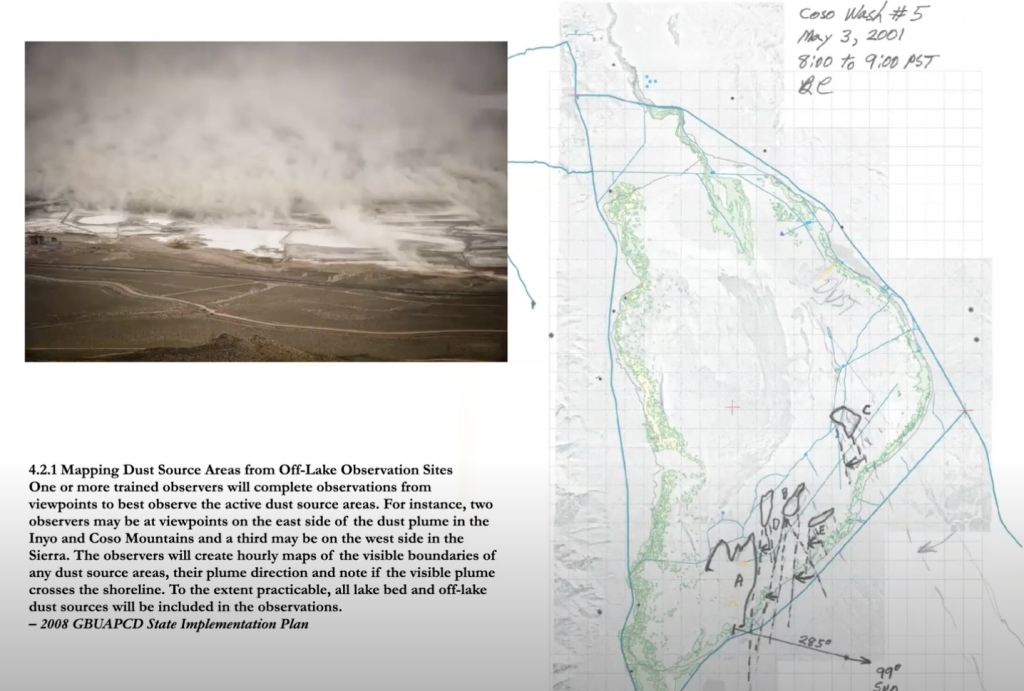

Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, Owens Valley PM10 Planning Area Demonstration of Attainment State Implementation Plan (28 January 2008).

In measurements of dust, for example, you see a protocol for hand drawing dust storms (a protocol adapted by an engineer-slash-landscape-architect). This was an important data set, but it was other modes of measuring dust, such as tracing it with ATVs & GPSes that were translated that directly into the form of the lake.

In fact, it feels like the entire 50 square mile extent of dust controls was made entirely under the influence of technical measurements. There are also some remote dust control sensors—this is a live kind of measurement of the dust that I screen captured. There are also various habitat models and ways in which they rationalize and understand what’s happening and what should happen.

I think this is obviously a way in which we need to proceed in this world—we need to do it with a whole set of measurements—but it also can produce strange results if it’s the only thing that’s guiding our practice and the only light that we follow. We end up, maybe, with a world that’s quite different from the world we set out to save or what we wanted to protect.

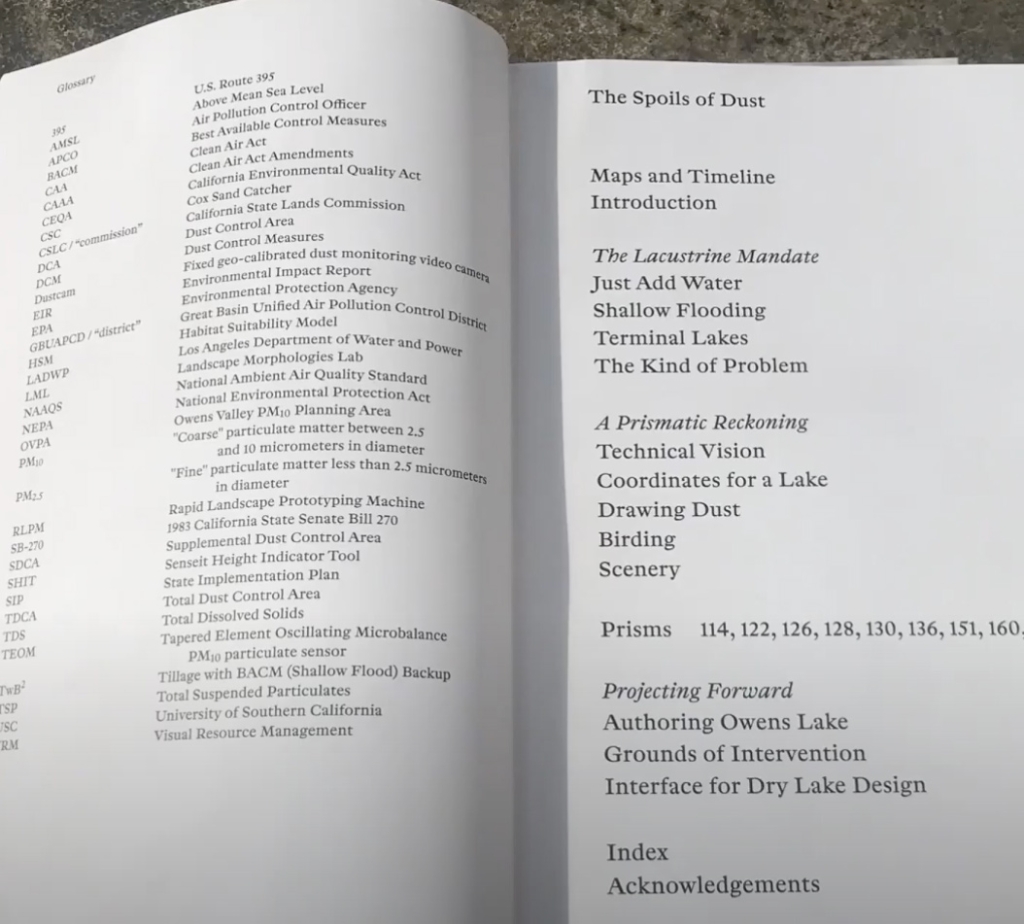

My work has been interested in what role a corporeal experience, an on-the-ground experience, plays in these kinds of technical landscapes. Does it matter how it looks to humans, for instance? What significance does it have as a kind of experiential architecture? And so one section of my book, The Spoils of Dust, looks at three subjects—dust, birds, and scenery—and studies how the corporeal experience, and particularly field observations, including very technical field observations, inflect into the landscape making. Our bodily experience has a surprising kind of significance and collateral effect and bias.

The Spoils of Dust: Reinventing the Lake that Made Los Angeles—TOC.

Citizen birding, for example, has had a really powerful effect, in part because the lake was transformed from a dry lake into a kind of drive-in lake—because it has a network of roads. You can monitor and count all of the birds within a day, with a small team. It has driven that transformation of the lake.

I think that corporeality—the ways in which our body becomes implicated in these landscapes—inflects all sorts of interesting things into it. Political, ethical, and aesthetic dimensions become part of the process, and it’s just inevitable that it becomes part of it but it’s rarely recognized and acknowledged.

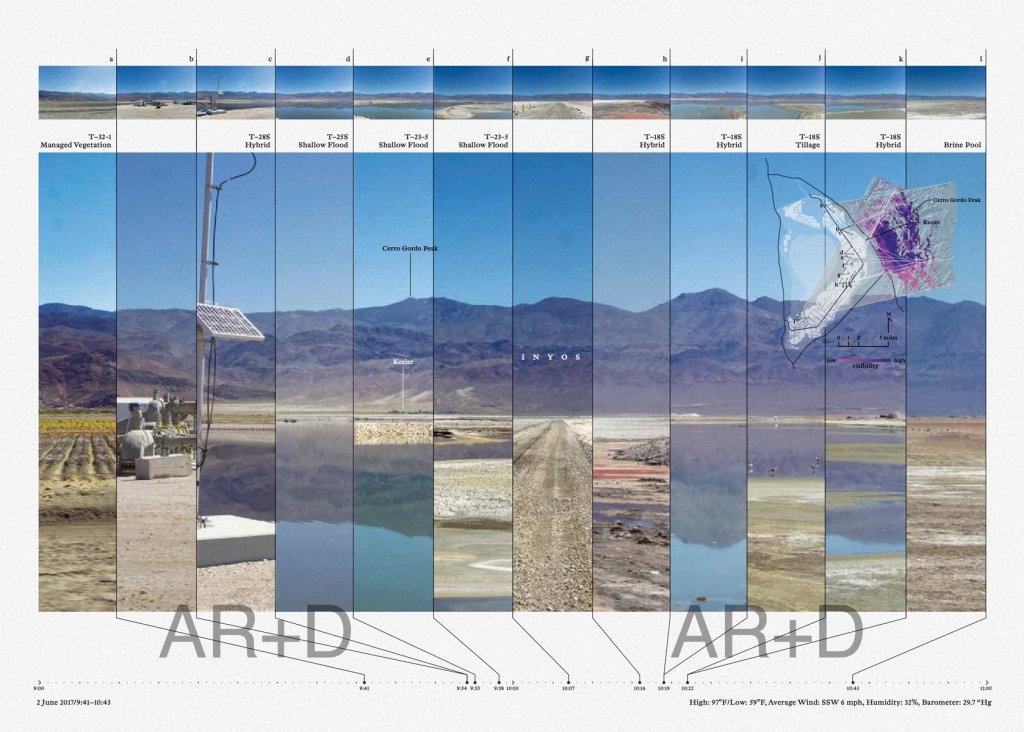

Meanwhile, the actual scenic experience, which is supposed to be an obvious aesthetic experience, besides the actual field observations, is probably the strangest and most illusory of all—and becomes a kind of bizarre prism of experience that even fewer people are paying attention to, or understanding, especially in these radically transformed landscapes.

High: 97°F/Low: 59°F, Average Wind: SSW 6 mph, Humidity: 32%, Barometer: 29.7 “Hg

Some of my research is on how we understand the experiential architecture of this place, and how we embrace the inevitable influence of (and impurity of) our corporeal experiences within technical landscapes, that are increasingly dominating our life and our sightlines. We live within infrastructure more than ever; infrastructure is supposed to be underneath everything but really it’s everything that we live around. So how do we design for this strange influence, often at odds with logic and economy?

This is a bit of context for my glass of water and how I look at things, at times. I wanted to set up a glass of water as a simple and convenient waterscape in my backyard and observe and see how I responded to it using some of the context in my own practices.

I live in a house built in 1911, when Los Angeles was relying almost solely on its river for drinking water, so I filled up the glass of water with LA River water and I placed it on a railing in front of a picturesque view in my backyard. I arranged it to align with Mount Baldy, the tallest mountain in LA County, and employed two observation methods. The first is a time lapse camera which you see here, borrowed from my river lab, to film it for a month, and the second and primary method was an intention exercise that the experimental filmmaker James Benning popularized among a few folks around here called “Look and Listen.” The exercise consists of just that—which also means no photos, notes, or talking, just paying attention for a period of time—and seems like a pretty radical practice these days. I think it’s exceedingly important that we do this, especially landscape architects—they need to pay attention to the landscape that they plan to alter. I wasn’t sure what would come of the vessel of water, but three things came forward of various interests.

One was that, upon later reflection, I noticed the extent to which I changed my environment to accommodate the glasses as a visual device. I cut down my hedge with my battery-powered trimmer and spent quite a lot of time doing that. I rearranged my furniture to accommodate the ergonomics of my body in this viewing device that I carefully aligned with this mountain, 35 miles in the distance and about 7,000 feet up. And overall I found that I wasn’t actually that interested in looking into the glass as a visual device—so maybe your screen saver for is not going to be popular—but it underscored the power of the potential of a sightline, and my interest in it, just as a person to set it up. I think what was more interesting is when I set the water glass on the railing it immediately informed me that the railing wasn’t flat and, in the context of the exercise, I sort of felt like the glass of water was already doing my job; it was a kind of environmental measurement device. It easily measured slope, rainfall, and evaporation rates. After a long pine needle fell into it, it functioned as a crude windvane; there’s a longer one that comes later.

And, three, as minerals and materials and organic life accumulated I realized that I made a kind of terminal lake like Owens Lake. It was a water body with no outlet, akin to salt lakes—they’re often perceived as stagnant pools of death, with noisome visuals and smells. In fact they’re places of abundant life (but also death for that reason) and, agitated by a pine needle, I watched the bubbles rise and plants grow. It lured birds I’d never noticed before and yet remained undiscovered by mosquitoes, and as it evaporated away its ecology appeared more intense and precarious. Inexplicably, the glass moved gradually to the right.

So for me this cross-wiring of a landscape and environmental sensor was of particular interest. As we increasingly modify and manage our landscapes, and ones that are within the sight lines of more and more people, the corporeal experience of these places inflects through us and changes our behavior, and has an outside influence on how we make and remake the world of even the most technical places. Of all the elemental things in our landscape, water is perhaps the most conducive to focusing our experience and directing us to certain, even important, conditions. Consider the wandering edge of a terminal lake or the bleached-out conditions of a drying reservoir.

I bet it’s also one of the most beguiling elemental landscapes for us, and that brings its own seemingly arbitrary consequences. On the last day of the month, I felt an urge to try to look and listen with clear water and with a topped-off water surface, so I overfilled the glass with more river water, dumping its contents and ecologies, and enjoyed the visual splendor of a sterile and clear freshwater lake.

Thank you.